Sherlock Holmes and the Genius of Nailing Stuff Down

With a Little Help from Thomas Carlyle, the Legendary Detective Pinpoints What It Takes

Getting at the truth on a consistent basis requires a number of specific skills and habits that I’ll explore with How True. But it also demands a way of engaging the world that Arthur Conan Doyle attributes to Sherlock Holmes in the first of several novels he wrote about the legendary detective.

After describing Sherlock’s meticulous examination of evidence, the narrator, Dr. Watson, quotes him as saying: “They say that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.”

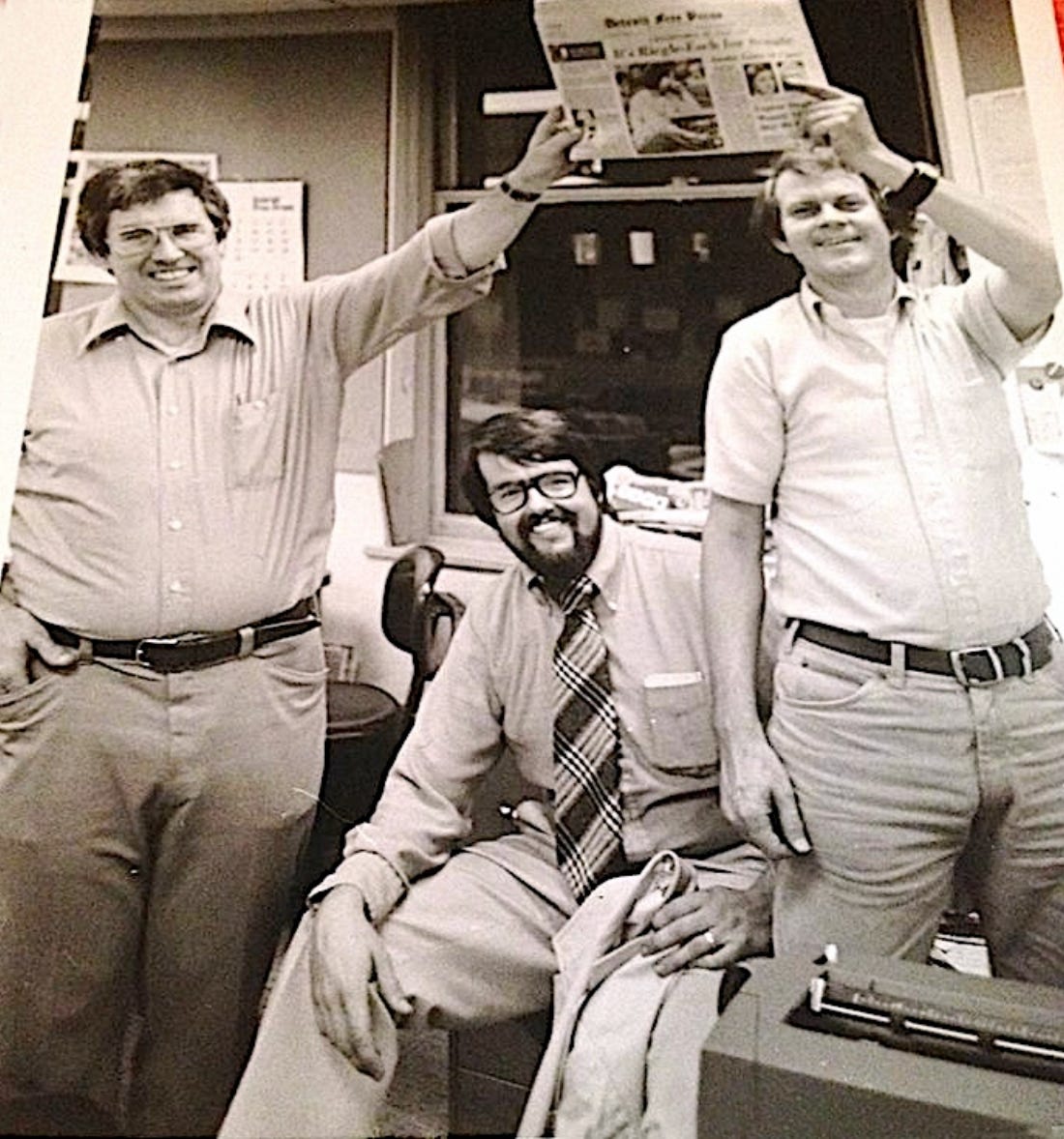

I know this not because I’m a close reader of Sherlock Holmes mysteries (I’m not), but because my former Detroit Free Press colleague John Gallagher recalled reading the quote in “A Study in Scarlet,” published in 1887.

Gallagher argues that the maxim applies every bit as much to journalism as detective work: “I think maybe all reporters fear getting something wrong above all else, even above getting scooped by the opposition. So we learn to take great pains, not just to spell names correctly and get dates right, but to check every angle, asking that one extra question.”

I’m still reading my dog-eared library edition of “A Study in Scarlet.” But it’s clear that Sherlock was the kind of detective who took great pains, with his tape measure as well as his magnifying glass, to pursue every angle he could find in pursuit of the truth.

I’m also a newcomer to the work of Thomas Carlyle, the 19th Century philosopher who is credited with the idea behind the Sherlock quote. Carlyle argued that success in any field is more a matter of diligence and process — taking pains — than innate brilliance.

Taking pains to extremes. Good extremes.

In my experience, the king of taking pains in journalism is the late Billy Bowles. In the 1960s, while covering the South Carolina state legislature for the Associated Press, Billy created a separate index card for every piece of legislation introduced. With no computer tracking in those days, Bowles became the go-to source — and not just among reporters — for the details of South Carolina law-making. Taking pains!

Taking pains does not necessarily carry with it unlimited patience or the sufferance of those thought to be fools. At some point, upset with a decision by a supervisor, Bowles took his card file to what I believe was the Gervais Street Bridge near the state house. Before anyone could stop him, Billy launched those index cards on a southeastern cruise, floating down the Congaree River never to be consulted or updated again.

For Bowles, taking pains also included a seven year investigation into conman David Davis, who posed at various times as a CIA agent, a Vietnam veteran and a college football star. When his wife died in 1980, he claimed she had fallen off her horse. Bowles suspected Davis had killed her and dug up evidence that led to his murder conviction, nearly a decade after her death. The case was recounted in both a documentary and a made-for-TV movie.

Taking pains is often a matter of developing routines to be followed day after day. Since there’s nothing like spelling a name incorrectly to undermine the credibility of a story, it’s a pitfall good reporters take pains to avoid.

There’s an app for that.

Gallagher, my Sherlock tipster, developed an app for that. At the conclusion of each interview, he’d ask the interviewee to print their name in legible, block letters in his notebook.

I followed the same routine, especially when reporting overseas in countries where I relied on interpreters and fixers for so much. But not the spelling of names. For that, I handed over pen and notebook to the subject of my interview.

Maybe because it changes every year, sometimes people even get their own ages wrong. Former Free Press editor Joe Grimm tells a tale of dueling ages: one age in the story and another, for the same person, in the caption of an accompanying photo.

As Grimm points out, the benefit of the doubt in such circumstances is often awarded the reporter. But Grimm took pains to contact both the reporter and the photographer in an effort to resolve the discrepancy. The reporter insisted he was right. The photographer described the pains he took: Asking the person he photographed to write not their age but their date of birth in his notebook. All of which provided Grimm with an easy choice as deadline approached.

Taking pains beyond journalism

Gallagher and Grimm have both taken their fact-checking beyond the world of newspapers. With his memoir, Rust Belt Reporter, which I reviewed here, Gallagher relied on newspapers.com and a personal diary to make sure he got the details right.

A journalism professor at Michigan State University, Grimm has worked with students to publish a series of “Bias Busters” books aimed at getting at the truth of the matter across a wide range of topics.

Before publication, the content of each book is reviewed by readers knowledgeable in the topic addressed by the book. That means if you spot errors in their latest book, 100 Questions and Answers about the U.S. Catholic Church, I’m partly to blame.

About that quote

In framing his ideas about the importance of taking pains, Carlyle was presumably focused on neither journalism nor detective work.

Students of his work suggest he had something more sweeping in mind: Life itself.

Coming soon

In an upcoming post, I want to write about an especially important imperative in nailing stuff down: Checking the clips. Or as it might be expressed outside the newsroom: Reading the directions or going to school on what’s gone before. It’s not just a journalism thing, as I discovered in preparing for prostate cancer surgery. If you’ve got a story that involves checking the clips, in or out of journalism, please send them my way at bmitch (at) gmail (dot) com.

Nicely done, Sherlock