It was 60 years ago this summer that I got my first job as an intern reporter at The Day newspaper in New London, Ct. I was 16.

The Day’s offices on what would be renamed Eugene O’Neill Drive became my home away from home for the next four summers. It was one blissful byline after another until one day in July 1969. The paper’s top brass ordered up a feature story about the 40th anniversary of the city turning over land to the government to create a new campus for the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. It was the kind of puff piece that veteran reporters would shun. So the assignment went to the youngest reporter in the room. Me.

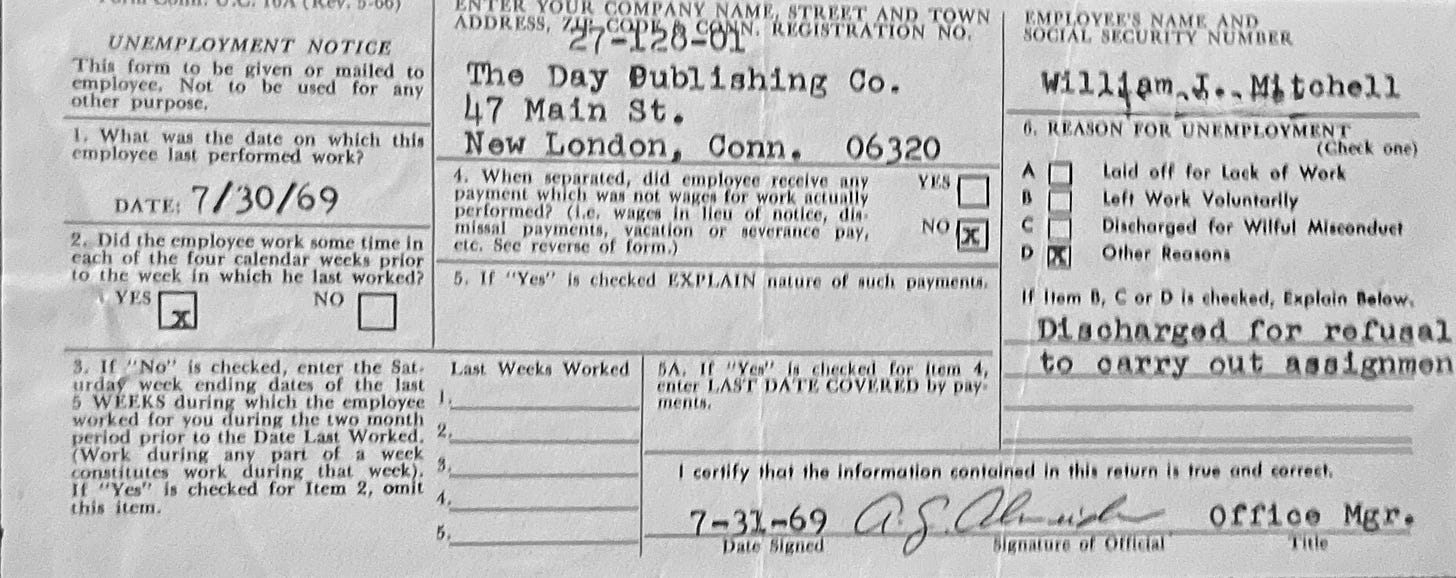

Researching the story, I discovered that the most interesting and significant angle was the Academy’s repeated landgrabs over the years. So that’s the story I wrote. Not what we had in mind, said city editor John Foley. I refused to budge and was fired. I’ve been shown the door a couple of times since but never as eloquently as I experienced that day in the publisher’s conference room: “Beverly will make out your check.” (The incident is documented in the chapter titled, “Rebellion,” in Greg Stone’s history of The Day.)

Luck, Mentors and the Basics of Nailing Stuff Down

Despite the painful outcome of my clash of facts and authority, I learned a lot at The Day — all the basics of nailing stuff down and some of what it takes to tell stories in ways people might want to read them. The paper provided me with smart mentors, reporters like Stone and Morgan McGinley and the late Stan DeCoster.

Most of my posts to HOW TRUE will relate the stories of others who’ve found promising pathways to facts, but friends on Substack tell me that it’s best to start with something personal about my own journey.

My good luck with internships continued the next couple of summers at the St. Petersburg Times and the Washington Bureau of The New York Times. I got the Times job only because of Jim Naughton, who graduated from Notre Dame ten years ahead of me and turned my tour of the bureau into a job interview. Jim became a close friend and mentor until his death in 2012. Several staffers in the Times bureau had worked for the Detroit Free Press and paved the way for my first full-fledged staff role there.

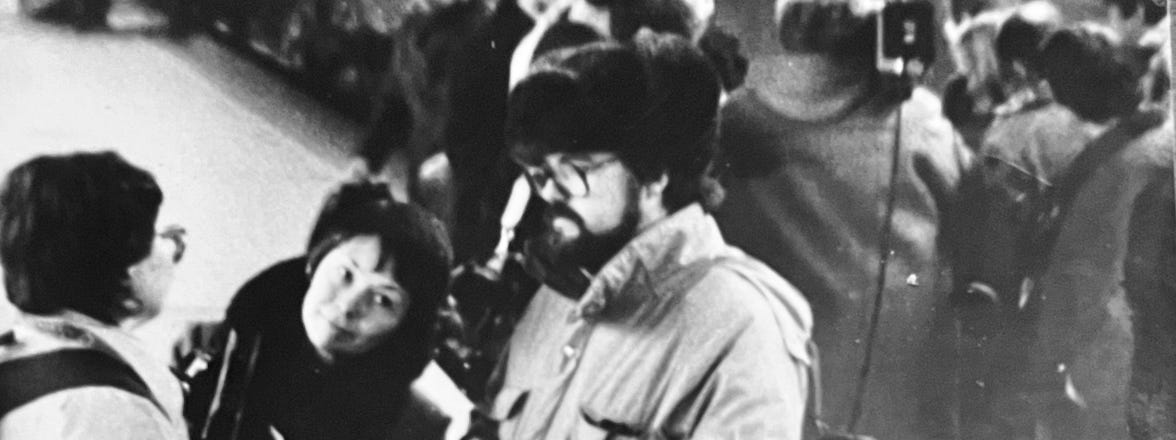

A dozen years after being fired by The Day, in the early 1980s, I found myself in another vortex of fact and power when I became the Eastern Europe correspondent for the Free Press and Knight Ridder Newspapers. The Solidarity movement was mounting a serious challenge to Soviet control of Poland, but the sources of information — state-run TV, radio and newspapers — were still controlled by the government.

If The Government Says It’s True, It Must Be False

A cultural phenomenon took hold: If the official media is reporting that something important is true, it’s almost certainly not. An example: After martial law was declared in Poland in December 1981, Trybuna Ludu, the government-controlled newspaper, praised the decision by General Wojciech Jaruzelski to crack down on freedom as a requirement of order. The paper described the population’s reaction to martial law as calm, welcoming the restoration of order. It didn’t take much reporting to figure out that, in fact, the opposite was true.

A decade later, I stepped into another new world: Silicon Valley. Leading the team that built one of the first fully digital newspapers, Mercury Center at the San Jose Mercury News, I began an apprenticeship in the unpredictable world of online facts. Later, at the Poynter Institute of Media Studies (where Jim Naughton had become president), I edited Poynter Online and sat in on as many seminars as I could. Among other things, I learned from Bob Steele, Kelly McBride and Keith Woods that ethics done right opens as many doors to truth as the most inventive investigative tool.

Back to Poynter

I retired from Poynter in 2012 but found myself back there last month for a seminar that prompted this newsletter exploring the stories and strategies of nailing stuff down.

As I mention in my welcome email to subscribers, I’ll leave the ranking of truthiness to Poynter’s Politifact, the initiative that Bill Adair kicked off in 2007 with the unforgettable ranking of “Pants on Fire!”

Angie Drobnic Holan, who succeeded Adair as editor-in-chief of Politifact, is now the director of Poynter’s International Fact-Checking Network. As she argued in this piece in April, the world of fact-checking faces a major turning point this year. Government funding for international fact-checking has been slashed, and Facebook and X have eliminated fact-checking just when it’s needed most.

Politicians like Donald Trump and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán are twisting reality and distorting the truth in ways that make Wojciech Jaruzelski almost look like a small time fibber. I welcome your help in finding and telling stories that track pathways to facts. How, in other words, to nail stuff down.

I wonder if the folks who ended your time at The Day ever had second thoughts about that assignment, the story you produced, and their reaction to it. Keep doing what you're doing to nail stuff down.

Love to see you here, Bill. I will share with my friends, many of whom are already your friends. I have been noodling to find an angle on my own Substack, in which I plan to focus on truth. Currently I am calling it the Noetic Cafe, but that is likely to change. I look forward to continuing to learn from you.